Turkey's unchanging ten-year policy: Incentives for bosses and unemployment for the people

A crisis period sees unemployment peaking again. With the government’s employment and incentivization packages filling the bosses’ pockets, what remains for working people is yet more unemployment and poverty.

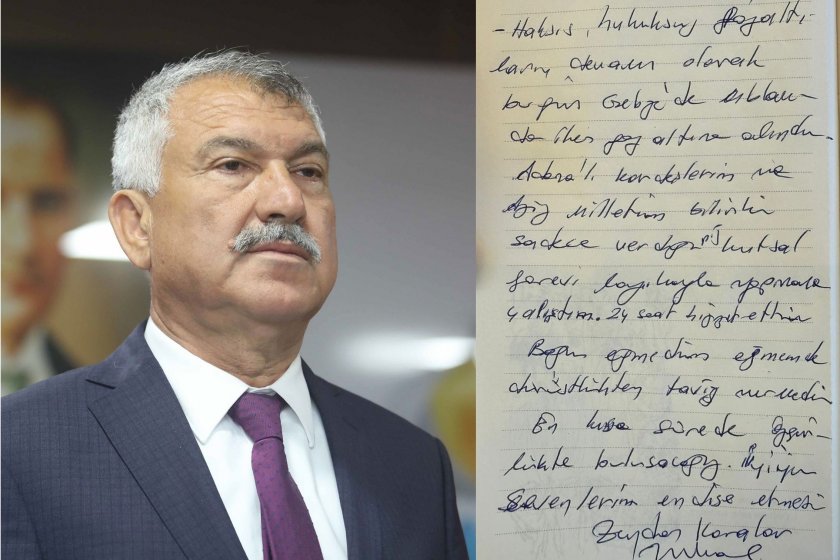

Fotoğraf: DHA

Zeliş IRMAK

Cem ŞİMŞEK

İstanbul

The economic crisis that began to make itself felt in the second half of 2018 has led to millions of workers and wage earners being employed under the threat of unemployment, while millions of others are struggling to stay alive due to unemployment. We encountered an increase in the number of crisis-related suicides last year for such reasons as unemployment and unpayable debts.

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI)’s official figures, unemployment has once more broken through fourteen per cent. Another unhideable truth is that the true unemployment figures (wide ranging) are much higher. Unemployment has reached this extent in the most recent period of economic crisis that broke out towards the end of 2008 and increased in severity in 2009.

Why were the employment and incentivization packages the government announced over the past ten-year period and why was the “Nationwide Employment Mobilization” proclaimed in 2016 incapable of solving the unemployment problem? Where did the incentives that were given go? We picked through the government’s employment policy making the odd reminder and asked for proposed solutions for unemployment from Istanbul University Faculty of Economics Faculty Member Associate Professor Dr. Murat Birdal and Labour Party General Chair Selma Gürkan.

WHAT WAS IN THE INCENTIVIZATION AND EMPLOYMENT PACKAGE PROCLAIMED IN 2009?

Unemployment hit record levels in February 2009 at 14.8%. 2009 and 2010 also saw the introduction of employment and incentivization packages for reducing unemployment that trended well above ten per cent throughout 2009. The country was split into four basic regions and incentives were set by region under the Incentivization and Employment Package proclaimed in June 2009. The aim of the package was to promote investment in regions where there was heavy unemployment and alleviate unemployment.

Companies were given tax reductions by region, the employer’s share of employee’s insurance contributions was met by the state and sites were assigned and loan interest support provided for investments targeting the high-unemployment third and fourth regions. Exemption from customs duty and VAT was also introduced for large-scale investments.

For those classified as “large projects,” a contribution rate of thirty per cent was provided for first region investments, while this was seventy per cent for fourth region investments. By way of example, for a ten-million lira investment, this incentive amounted to the state contributing three million if it was made in Gebze and seven million if made in Dersim.

INCENTIVES HAD LIMITED EFFECT ON EMPLOYMENT

Following the 2009 crisis, there was a 13.2-point increase in the growth rate spurred by foreign investment and it reached 8.5% in 2010. However, increased production had a limited effect on unemployment. With unemployment standing at 14% in 2009, it fell by a mere 2.1 points in 2010.

PACKAGE DID NOT SUFFICE FOR BOSSES WHO WANTED MORE

Finding the incentives to be inadequate, the bosses produced a report in December 2009 and submitted “proposals” for reducing unemployment with fresh demands from the government. According to the bosses, the way to bring unemployment down was to expand flexible and insecure working, eliminate the right to severance pay and use the unemployment fund in a way that deviated from its purpose:

The limitations on taking paid leave should be lifted and flexible forms of working such as part-time work and work sharing should be encouraged,

- The severance pay burden should be reduced,

- Severance pay for companies that have no choice but to lay off workers should be paid from the unemployment fund,

- Bosses should be given wage subsidies from the unemployment fund, and

- Private employment offices should be brought into being and “harsh” measures relating to sub-contractual working should be done away with.

SIMILAR STATE OF AFFAIRS IN 2012-2013 AS UNEMPLOYMENT INCREASES IN TANDEM WITH INCREASED GROWTH

Incentivization and employment packages were also brought into life to decrease unemployment in 2012 and 2013. Bosses were afforded such opportunities as VAT and tax exemption and reductions, insurance contribution support, reduced interest rates and the assigning of sites for investment under the package implemented in June 2012.

Subsequently on 12 March 2013, state employment agency İŞKUR initiated the “On-the-Job Training Programme.” All bosses who employed at least two insured workers were able to benefit from the İŞKUR programme. The incentives varied by sector.

Bosses were enabled to pay no employer’s insurance contribution for a period of 30-42 months in return for employing participants within three months as of the end of the programme. This amount unpaid by bosses was met from the Unemployment Insurance Fund. Payments made by the employer were deducted from tax.

With the growth rate, 4.8% in 2012, increasing to 8.5% in 2013, the rate of unemployment, which had been expected to fall, rose by 0.5 points as against the previous year to register an increase of 9.7%.

“NATIONWIDE EMPLOYMENT MOBILIZATION” ALSO BENEFITS BOSSES

A similar state of affairs prevailed in 2016 in which the state of emergency was declared and in the subsequent years dominated by decrees with the force of law. With the growth rate at 3.2% in 2016, it rose to 7.4% in 2017. However, unemployment, standing at 10.9% in 2016, remained stable at 10.9%.

Well, what incentives were provided in this period? Adjustments were made to the “On-the-Job Training Programme” in February 2016:

- The duration of the programme was increased from six months to one year,

- Wages paid to participants were met in full by İŞKUR,

- The quota limit that had been set at ten per cent was raised to thirty per cent for bosses who promised high employment (In its form before the programme was adjusted, trainees could be taken on at up to ten per cent of employee numbers), and

- High school students were also included among potential participants.

As to the hired worker and private employment office measures the bosses had mooted following the 2009 crisis, these came into force in October 2016.

In 2017, the government declared the “Nationwide Employment Mobilization.” However, the incentives once again showed the government was mobilizing for the bosses and not the unemployed. With the bosses supposed to fork up 2,177 lira for each minimum wage worker they took on, they only had to pay 1,404 lira. The remaining 773 lira in contributions and tax obligations was met by the state.

By the end of the year the new incentives were seen not to have prevented unemployment. With the minimum wage also raised from 1000 lira to 1300 lira in 2016, the lion’s share of the 30% increase that had been made was also met by the state.

CRISIS AGAIN, INCENTIVES AGAIN, HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT AGAIN

The economic crisis that began to make itself felt from the second half of 2018 brought with it a flurry of government announcements of incentivization packages with the bosses in mind. However, far from reducing unemployment, these incentives did not keep it from peaking at 14.7% in the 2009 crisis. The aim today of the government, which brought in flexible working and hired workers after 2009, is to transfer severance pay, which workers call “their guarantee and final stronghold” to the fund.

THE SHARE OF PRODUCTION RECEIVED BY WORKERS AND WAGE EARNERS IS FALLING, THAT OF THE BOSSES IS INCREASING

On the other hand, there has been a constant decrease in the share of growth going to the millions of workers and wage earners since 2014. While in 2014 the share of national income of the 20% receiving the lowest share was 6.6%, in the same year the 40% segment constituting the low-income group got a mere 17.5% of national income. The richest 5% segment, by contrast, received an 18.4% share of national income.

Coming to 2017, while the share of national income obtained by the poorest 20% was 6.3% and the share of the poorest 40% had regressed to 16.9%, the share of the richest 5% had risen to 21.3%.

MURAT BİRDAL: CAUSE OF STRUCTURAL UNEMPLOYMENT IS AKP POLICIES

Stressing that the structural unemployment problem in Turkey was a result of the policies of privatization that the AKP had implemented since 2002 and the transformation that had taken place in agriculture, Istanbul University Faculty of Economics Faculty Member Associate Professor Dr. Murat Birdal said, “In the end, even in periods of growth in which inflows of hot money to the country have been at their most intense, unemployment has pushed into double figures. We have thus become acquainted with the notion of jobless growth.”

Birdal summed up the relationship between the jobless growth model and the AKP’s economic policies as follows:

“In previous periods, the high proportion of the total population employed in agriculture and public economic enterprises limited the effect of fluctuations on employment. The structural transformation the IMF imposed on Turkey and the AKP subsequently implemented having obtained the support of the West goes a long way towards accounting for the situation we encounter today.”

“PROBLEM IS NOT SOLUBLE THROUGH MONETARY POLICY AND INCENTIVES”

Stressing that the unemployment problem was not soluble through monetary policy tools and incentives, Associate Professor Dr. Murat Birdal said, “Initially, the education system must be restructured from the ground up to create a workforce that can adapt to the innovations of rapidly developing technology. Supporting agriculture and husbandry is an indispensable situation. I believe that public enterprise, which plays a major role in establishing industry and reducing regional imbalances, can also perform a major function in the future.”

SELMA GÜRKAN: THE AKP IS A PARTY GEARED TO CAPITAL IN TERMS OF ITS POLICIES

Assessing growth and employment policies, Labour Party (EMEP) General Chair Selma Gürkan stated that the natural consequence was being experienced of the growth model based on flows of foreign capital and unearned income. Pointing out that the economic model was based on cheap labour, Gürkan stressed that the AKP had turned the country into a cheap labour paradise. Indicating that Turkey was noted for long working hours, arduous working conditions, work manslaughter and low unionization, Gürkan emphasised that the government was a party geared to national and international capital in terms of its economic policies, with the reality of “social welfare” veiled over.

Saying the basic aim of incentivization packages was to rescue companies, Gürkan pointed out that working people had been condemned to unemployment.

“THERE IS UNEMPLOYMENT SO THE COGS TURN TO BENEFIT THE CAPITALISTS’ INTERESTS”

Saying that unemployment was capitalism’s structural problem and an indispensable feature of the order, Gürkan summed this up as follows:

“The unemployed have always been and will continue to be kept on hand as the capitalist order’s reserve army of labour as a constant element of threat to the employed members of the working class. The ruling party has, with the policies it implements so the cogs turn to benefit the capitalists’ interests, constantly increased unemployment. As unemployment rates increase, workers’ and wage earners’ working and living conditions have grown ever worse. Without prompting a reaction, ruling parties proclaim packages of assault on workers and wage earners as if situations in workers’ and wage earners’ favour so as to implement them. The AKP does this, too.”

“WORK MANSLAUGHTERS ARE THE CONSEQUENCE OF FLEXIBLE, RULELESS EMPLOYMENT”

Saying that bosses today are striving to employ workers at “zero cost,” Gürkan said the turn had now come of severance pay. Gürkan said that another major consequence of the introduction of flexible, ruleless, unmonitored employment at the bosses’ behest was the work manslaughters that cost the lives of 3-4 workers a day. Gürkan pointed out that a significant portion of the working class had also been made deorganized over this process.

Stating that it was essential for the class to attain unity in a period in which workers were threatened with unemployment, Gürkan underlined that the unemployed and refugees, seen today by workers as a threat, were part of the working class.

“DAY-TO-DAY DEMANDS MUST UNITE AROUND A LINE OF POLITICAL STRUGGLE WAGED FOR CLASS INTERESTS”

Stating that the struggle being waged against making workers and wage earners foot the bill for the economic crisis was related to the struggle against capitalism, EMEP General Chair Gürkan stressed the need for workers and wage earners, in the face of the bosses’ wish to condemn workers to privation wages with collective agreements on offer, to struggle for a human living wage by rejecting such offers and not recognizing contracts that have been signed.

Gürkan also warned that the struggle waged for day-to-day demands needed to follow a united line in which the working class wages political struggle in class interests.

(Translated by Tim DRAYTON)

Evrensel'i Takip Et