Turning point in Germany

In the meantime, the blow from Ukraine, not being able to obtain the weapons it wanted from Germany, came that it did not want to see German President Steinmeier in Kiviv

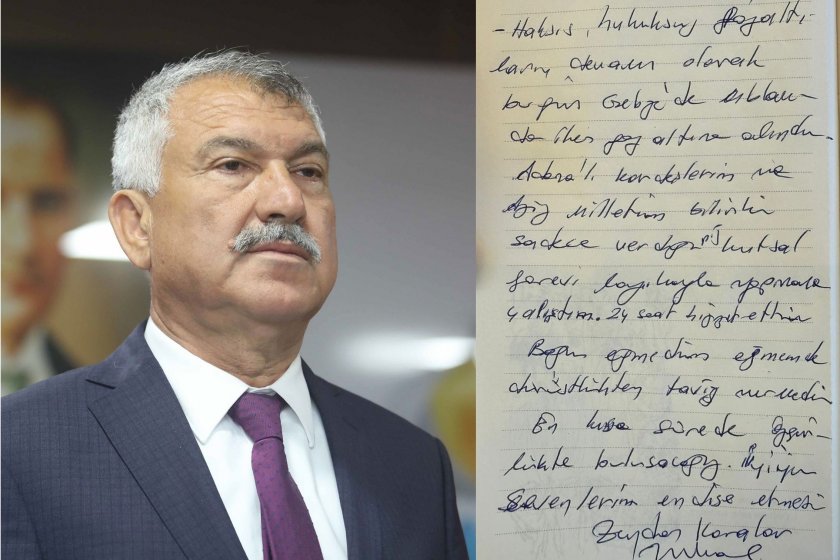

Fotoğraf: Olaf Kosinsky / Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA 3.0)

“It is a labour in vain to attempt to recapture our past: all the efforts of our intellect must prove futile. The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) of which we have no inkling.” says Marcel Proust. The past found me, in an unexpected moment, on the newspapers standing hanged in front of a buffet I passed by in subway by chance: Above forty countries had got together in Ramstein American base in Germany under the leadership of the USA, and Germany had approved of heavy arms aid to Ukraine. The smell of Berlin subway had also taken my mind to Berlin of 1990. To those days that East Berlin used to be still accessed through the control point of Charlie, that two governments still persisted officially but the wall had practically ceased to exist. There has passed exactly thirty two years since then. Many things have changed in Berlin, but the smell of the subway has remained the same.

Every one might define the 32 year long period differently from their own point of view. From my point of view, it represents the beginning and end of my youth evethough it consists of different periods in it; for some international relations specialists, the unipolar moment in world politics ; for some other specialists, the globalization of liberal system including the old Soviet block and China. All of these definitions are consistent and valid from their own point of views. It is not the validity of definitions here that I am interested in. Who looks at it, why and from which point of view? How are the points of views formed? How far does the time dimension formed by those points of views get stretched? It gains meaning in the construction of those points of views which events form an interruption, a turning point in the flow of time.

The speech that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz gave in Bundestag, three days after Russia attacked Ukraine, indicated that a serious fracture in time had occurred. The Chancellor articulated the end of the Policy for East, which his own party SPD took the lead of in 1970’s and later became German official policy, by the notion of “turning point” (Zeitenwende). Of the change, there are two characteristics striking the eye first: 1) A huge investment to be made on Germany’s weapons industry and armed forces (100 billion euros in addition to the current budget); 2) abandoning in the international relations doctrine the dogma that the economic cooperation leads to political cooperation. We will all together see what kind of consequences these changes will bring about in concrete politics, however, at this stage, what is not to be missed out is what sort of burdens and advantages, risks and opportunities these changes will bring about for which social classes and groups in Germany. Having been passing through an extraordinary period due to COVID-19 pandemic, how will Germany deal with the ever increasing cost of this war and the burden of new politics? Who will pay the price?

German foreign politics is also facing outside the country one of the most difficult tests in its contemporary history. During his Moscow visit in mid February, the Chancellor Scholz made just an Angela Merkel impression by implementing his basic promise to German electorate. It was repeated round and round, in the news and in the reports, that Scholz approached to the crisis with “fingertip sensitivity” (Fingerspitzengefühl), that Putin started to withdraw Russian soldiers from Ukraine border, the great political success of the Chancellor, the political influence Germany had as the biggest economic power of Europe. It is perhaps for this reason that the Russian attack on Ukraine has been the biggest blow also to Scholz. He had been clearly cheated on and even worse, he had been made a part of psychological war game Putin watched smirking. While hundreds of thousands of protestors fill up the streets of Berlin against Kremlin’s attack, the Chancellor was trying to maintain the control of the situation by his “turning point” speech. In the meantime, the blow from Ukraine, not being able to obtain the weapons it wanted from Germany, came that it did not want to see German President Steinmeier in Kiviv. While Baltic Republics and the leaders of Poland were posing with Zelenskiy, Germany was being politically isolated in Easter Europe.

This event reminds the memoires of young diplomat Bismarc, seated in the waiting room at the Paris Conference, to those who are familiar with the war of Crimea in the middle of the nineteenth century. Without a doubt, it is easier to determine that the time has changed than to determine what needs to be done in the new time. Before everything else, a new Policy for East means a new social and political contract. Always having a distance between himself and his own party, will Scholz be able to lead the biggest political transformation of his party? Would the new policy not require a new cadre? As a leader to be able to maintain the status quo and resembling Merkel in many ways, would Scholz be suitable for such a mission? The Chancellor, that Der Spiegel put on the front page with a title “What are you afraid of?”, had announced that he had been trying to prevent a nuclear war, in the interview published in the same issue. After this interview, once he changed the policy and decided to provide heavy weapons support to Ukraine, the public unavoidably started to question whether a nuclear war was approaching. Syrian crisis must have taught the leaders the price to be paid once they draw red lines and then they disregard them. But the memory does not follow logic. In order for Germany to form a new policy, it needs new historical analogies. Ramstein conferences, said to be continued, will be an important centre to produce these analogies.

Evrensel'i Takip Et